A microneedle patch worn just a few minutes at a time successfully desensitized peanut-allergic mice, new research shows.

By inserting the peanut protein into the skin, the microneedle patch may provide faster and more consistent dosing for allergy desensitization than patches that sit on top of the skin, researchers say. It next needs to be tested in humans.

In the study published in Immunotherapy, University of Michigan researchers applied a peanut-coated microneedle patch to the skin of peanut-allergic mice. The mice wore the patch for five minutes, once a week.

For comparison, a second group of mice received epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT), a patch that also delivers peanut protein, but must stay on for up to 24 hours a day.

After five weeks, the mice treated with the microneedles were desensitized to peanut, whereas the mice wearing the EPIT patch needed two months of constant patch-wearing to become desensitized.

“Our approach here was to try to improve on epicutaneous immunotherapy,” says Jessica O’Konek, PhD, senior author and a research assistant professor at the Mary H. Weiser Food Allergy Center at the University of Michigan. “We compared a minimally invasive, five-minute microneedle device versus a 24-hour skin patch, and found the microneedle device to be far superior.”

Moonlight Therapeutics, the developer of the microneedle patch, has met with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in preparation for launching a clinical trial in children and adults, planned for mid-2023. The Atlanta-based company received a $1.9 million grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) to study using the device for food allergy treatment. However, additional funding is needed to complete the trial, says Samir Patel, a chemical and biomedical engineer who is Moonlight Therapeutics’ CEO.

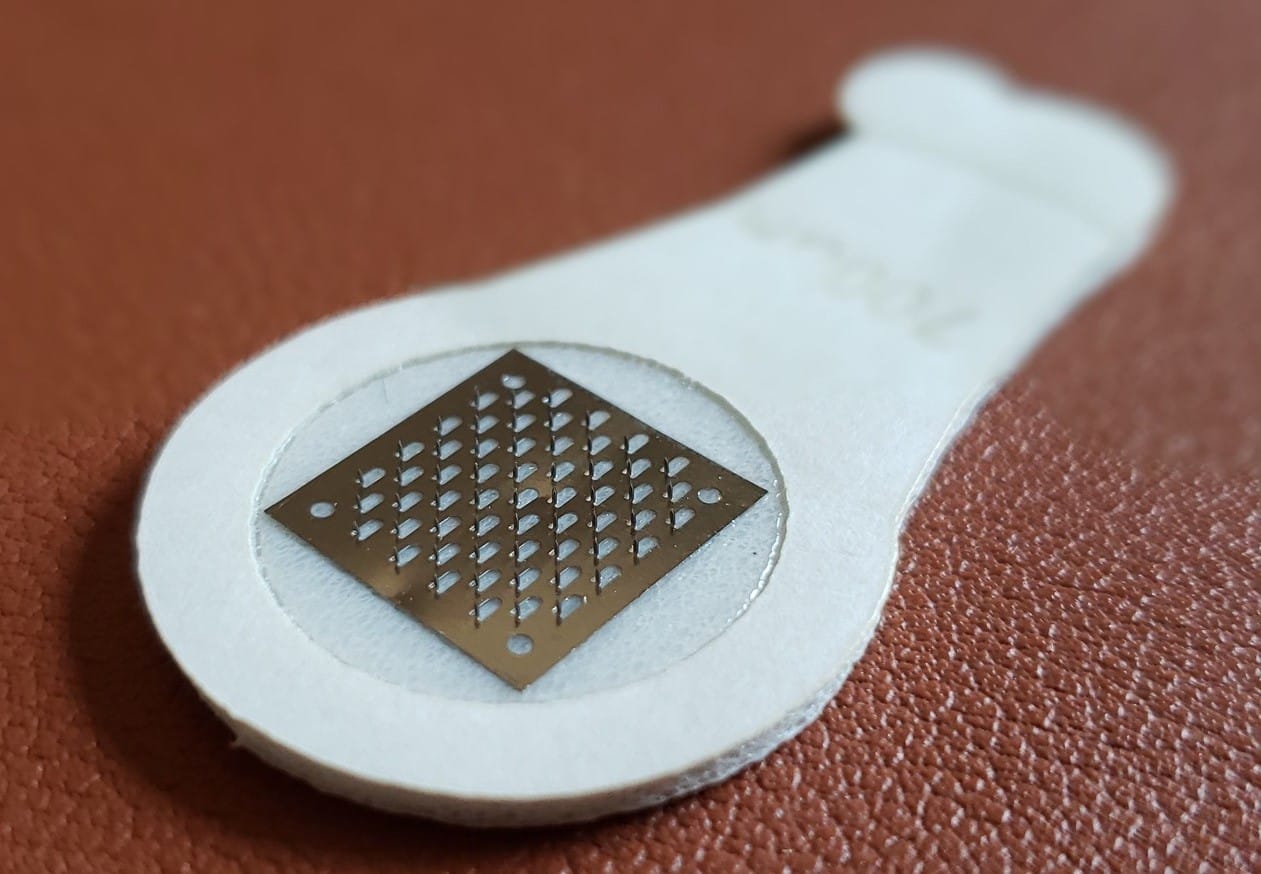

Food Allergy Therapy Picture

If the microneedle patch is shown to be safe and effective, it could eventually be used to desensitize children and adults with allergies to multiple foods. “One of the unique benefits of the microneedle patch is that each needle can be coated with a different allergen,” Patel says. Because of the way the allergenic protein adheres to each needle, the allergens can be kept separate from one other, without mixing, he adds.

Currently, Palforzia capsules for peanut allergy are the only FDA-approved food allergy treatment. Approved in children ages 4 to 17, patients taking Palforzia consume gradually escalating amounts of peanut protein over several months. In clinical trials, a majority of children could tolerate 600 milligrams of peanuts (about two peanuts) at the end of the build-up phase, which takes about six months. Children then stay on a maintenance dose indefinitely.

While it has a strong record of effectiveness, oral immunotherapy (OIT) does carry the risk of allergic reactions in the build-up. Researchers continue to look for alternate methods of desensitization, such as through the skin. But the epicutaneous immunotherapy (EPIT) approach is proving challenging.

Clinical trials have shown that EPIT has a good safety profile, but is not as effective as hoped. Clinical trials for DBV Technologies’ Viaskin Peanut patch found that after one year, 35 percent of kids ages 4 to 11 responded to therapy. Duration has proved helpful though. With three years of treatment, 52 percent could consume up to 1,000 milligrams of peanut protein.

In 2020, the FDA rejected DBV’s application for approval, raising concerns about the patch’s adhesion to the skin and the potential impact on efficacy. (DBV has modified and enlarged the Viaskin patch, and a new clinical trial is planned.)

Improving Skin Approaches

One drawback of an immunotherapy skin patch that sits on the skin is that it takes a long time to achieve protection from allergic reactions. This is likely because the top layer of the skin, the stratum corneum, acts as a barrier that prevents some protein from being absorbed, O’Konek says. There are also questions of dosing consistency. The amount of allergen absorbed can vary from person to person, impacted by age, genetics, and conditions such as eczema that affect how much protein gets through the skin barrier.

Patel says microneedles may be able to overcome some limitations. Like little darts, the microneedles puncture the stratum corneum, delivering the peanut extract into the dermis about 1 millimeter down, where it activates immune cells. “The skin is rich in immune cells. The microneedles let you access those immune cells in a very targeted way,” he says.

Also called a “dermal stamp,” the device contains 50 tiny needles, although it can fit up to 100, on a surface about the size of a dime. It was first developed as a new way of delivering vaccines, although it is not yet approved for that use. The length of each needle is about 0.5 millimeter, or less than half the width of a quarter. When applied to the arm or back, Patel says the sensation is similar to Velcro being pushed against the skin.

For safety, the dose that will be used in the human trials will be very small, about 25 micrograms, Patel says. (One microgram is about 1/1000th of a milligram, and there are 250 milligrams in one peanut.) “The low dosage used to elicit immune response is a potential benefit because if you need less drug, then it should translate to better overall safety,” he says.

In the Phase 1 human trial, the microneedle patch will be applied daily, Patel says. Response will be measured through blood markers indicating allergic reactions, while later trials will involve food challenges.

O’Konek found the research in mice exciting, since “it’s a totally different way of modulating the immune system.” Looking ahead, “the goal would be something that people could do at home. Unlike the patch that has to be worn for 24 hours, this would be something shorter, that they could put on and take off,” she says.

Related Reading:

Dupilumab Shows Success in EoE, Leading to Hopes for Approval

Palforzia OIT Sees Maturing of Immune System Over Time