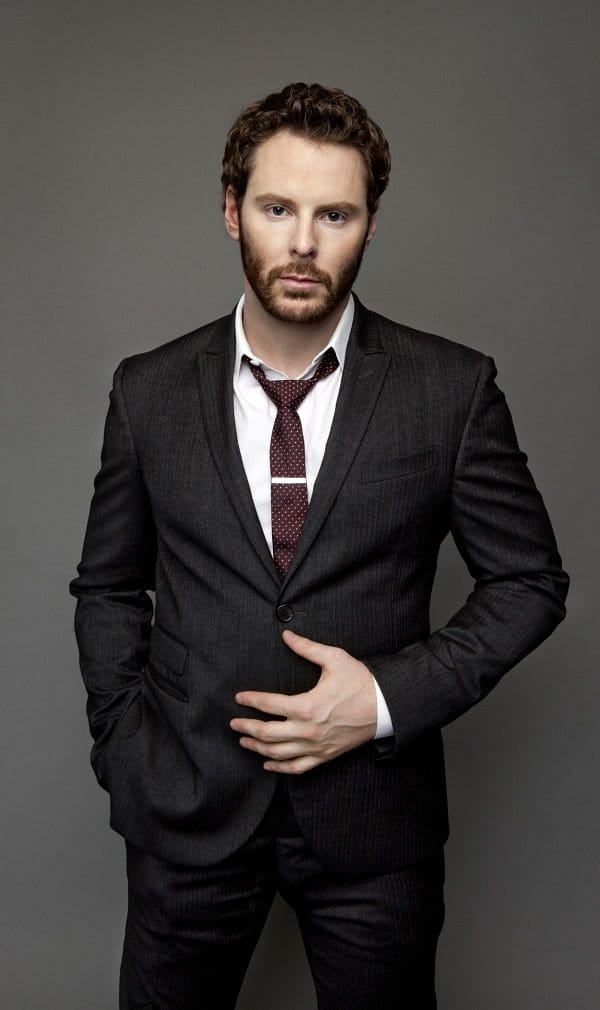

Dec. 14, 2014 – Medical research into finding a long-lasting food allergy treatment has been given a huge shot in the arm. Billionaire tech mogul Sean Parker, the former president of Facebook, announced in December 2014 that he is donating $24 million to Dr. Kari Nadeau and her team at Stanford University.

The funds will be used to create the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy Research, and to ramp up the scientific work of immunologist Nadeau and her team, as well as collaborators at other sites.

Parker and Nadeau have ambitious objectives. In a media conference call, they spoke of making “catalytic change” and moving toward a therapy that takes only one or two treatments, retrains the immune system at the cellular level – and lasts.

“The goal is really important to keep in mind,” said Parker. “It’s not just enough to come up with slightly better incremental improvements on the treatments that are out there, the goal is to achieve a cure.”

Parker, who famously started Napster before working with Mark Zuckerberg to make Facebook a global phenomenon, has a personal stake in seeking tech-style disruption in the world of allergy research. He’s at risk for anaphylaxis to several foods, including peanuts, other legumes, nuts and shellfish. He has needed emergency hospital care for both anaphylaxis and asthma – “my wife claims it’s been 14 times since we’ve been dating (they met in 2010) and now married. So it dramatically affects your life and, if you have a comorbidity such as asthma, it’s a much more severe problem.”

As the father of two young children, Parker is also highly aware of the genetic component of allergies. Referencing the breathing issues he’s had with asthma and seasonal allergies, and the risks from trace amounts of food allergens, Parker notes: “It would be incredible if nobody, including my children, ever had to go through this.”

Nadeau is definitely among the researchers on the forefront of finding a successful treatment for food allergy. The field began to move ahead with oral immunotherapy or OIT in which miniscule, then gradually increasing amounts of an allergen are fed to an allergic person with the goal of desensitizing to a single allergen.

But that therapy has not been without sometimes serious side effects and setbacks, such as a 2013 Johns Hopkins University long-term follow-up study that found a majority of patients who were supposed to be desensitized still having symptoms – sometimes serious ones.

This does not deter Nadeau, since her work has already moved beyond OIT on its own. “Oral immunotherapy alone is helpful in many patients, but it doesn’t work in everyone,” she said on the media call. Much of her success at Stanford in the past three years has focused on the combination therapy of anti-IgE medication (known by the brand Xolair) followed by OIT to treat up to five food allergies at once.

It appears the immunologist and the new research center are planning to move forward with new clinical trials as early as 2015. Although Nadeau couldn’t yet be specific, in a press release she says she views Parker’s gift “as the springboard to improve the lives of those adults and children with allergies through immunotherapy that goes beyond oral therapy.”

On the media conference call, she and Parker both stressed an intriguing fact about food allergy. “We know that there are some people out there who had food allergies when they were children but naturally lost those allergies,” said Nadeau. “So we know that the immune system can be turned off. It can become non-allergic. The big question is ‘how’? How can we do it?”

Her team will be looking for key biomarkers in those who are sensitized, and in those who become desensitized. “I think it’s going to take combination therapies, I think we have to be smart about collaborating (with other centers) – we need to collaborate and share data,” she says.

Parker speaks of a fascination with the workings of the immune system, and has also given generously to immune-based cancer research. Aside from expressing confidence in Nadeau’s abilities as a researcher and immunologist, he is impressed by the level of patient involvement at Stanford – the clinic has a waiting list of 1,500 would-be desensitization patients. For clinical trials, he notes, “patient recruitment is almost as challenging as the science itself.”

So will he join the trials at the center that will soon bear his name? “There are some things on the horizon that are very promising, and I’ll be the first in line to try them,” Parker said. “I’m confident enough, that I’m probably going to be one of the first people to enter those trials when they open.”

See Also:

- The Hunt for a Food Allergy Cure: Where Is It Heading?

- New Blood Tests Aim to Predict Food Allergies – and Severity