In June, Beth Garver’s daughter Amelia, affectionately known as “Lia,” completed first grade. The New Bern, North Carolina school hosted a drive-by graduation ceremony, and Garver beamed as Lia waved and cheered on her teachers, who were dressed up in grass skirts and luau shirts. Lia hadn’t seen her teachers in-person since the school shut down in March due to COVID-19.

“It took a lot for me to send her to a public school, period,” says Garver, explaining that she worried that her daughter’s multiple food allergies would not be taken seriously. The mother of two had worked closely with the school to make staff aware of Lia’s food allergies, and to get safety measures in place, such as added supervision for her daughter during meal time. By first grade, Garver was getting more comfortable with her daughter being in the classroom – and then the pandemic hit.

At the end of the drive-by graduation parade route, a staff member handed Garver an envelope from the school nurse. Inside was a letter advising that, due to Lia’s asthma and multiple food allergies, if the pandemic persisted, it would be better for the 7-year-old to stick with the online curriculum for the fall. If she wanted to return to the classroom, a doctor would need to clear it.

The letter frustrated Garver: “This just kind of felt like they were opting out.” She has good reason to want to see Lia in school, but is torn on the matter. When the school shifted to virtual remote learning before the summer break, Lia struggled. Garver and her husband were working from home at the time, and it was difficult to give Lia the structure that school provides. As well, the couple has been caring for their 4-year-old Max, with the daycare closed.

Still, even if the school hadn’t sent that letter, Garver would have been hesitant to send Lia back. Between her food allergies and the risk of COVID-19, the second grade classroom did not feel entirely safe.

Tough Calls on School

Typically, going back-to-school involves buying new backpacks and working out drop-off schedules. It’s taken for granted that children want to be in school, being taught by teachers and gaining life skills. For food allergy families, there are always discussions about food safety measures, cafeteria seating and epinephrine. But this year, with the COVID-19 pandemic, food allergy parents are weighing a tough decision: whether to send children back to school or virtually educate.

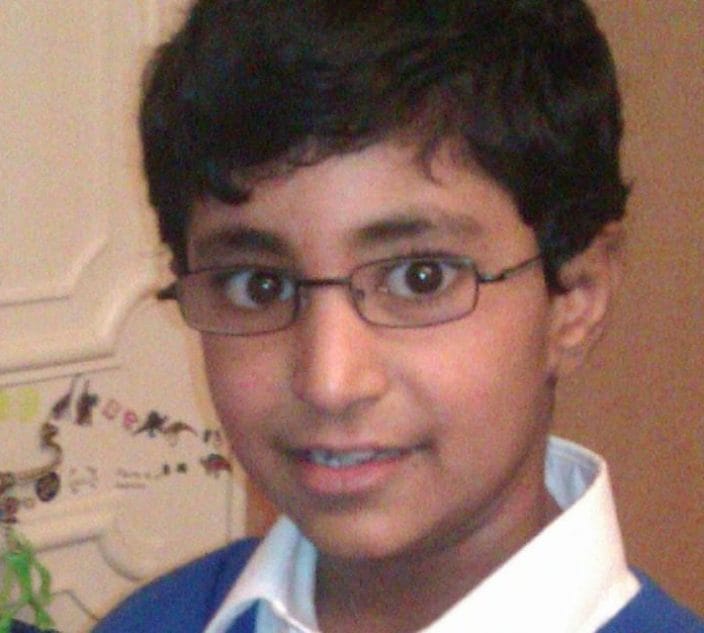

Dylan, Deacon and Owen.

On Facebook forums, the concerns of food allergy parents pour out. Some raise worries about the CDC’s recommendation that food be eaten in the classroom rather than the cafeteria, and how allergen exposure risks will be managed.

Like Garver, others are concerned about whether food allergies will be treated as secondary in the time of COVID-19. Lia experienced anaphylaxis at school in kindergarten, prompting Garver to work more closely with her teachers to develop an understanding of her daughter’s food allergies and the necessary precautions. “One of the added elements of stress of going back during the pandemic is that I don’t know [Lia’s] second grade teacher, and I’m not sure if she’s familiar with kids with allergies,” she says. Her conversations with school administrators haven’t lessened those concerns.

While some worry about food allergy accommodations, other parents are more concerned about COVID-19 ,and what measures schools are taking to reduce exposure risks. Although the rate of the disease’s infection in children has been lower than in adults, studies are emerging and much remains unclear. As well, research continues on how likely it is that infected children could transmit the virus to adults, even if not ill themselves.

Emily Busch Saganiec works as an ER nurse near Atlantic City, New Jersey and has seen multiple friends, coworkers, and some children contract COVID-19. At work, the mother of four wears safety goggles, an N95 mask with a particulate filter, a surgical mask and a face shield just to see non-COVID-19 patients. With COVID-19 patients, there is even more protective gear.

Saganeic’s 12-year-old Ryan has a dairy allergy and has previously had reactions at school. She wants to send her kids back to school, but remains unsure. “I have been lucky enough not to get COVID-19 despite taking care of COVID patients this whole time because of the extensive precautions I take with my PPE (personal protective equipment),” she says. “My kids are not going to be able to replicate that at school, and I wouldn’t want them to have to do that.”

Saganiec has told the school that her children will be doing in-person learning when fall classes start – but she’s “very much still on the fence.” “There is no ‘right’ choice,” she says.

Using Caution, Not Fear

Daryl Jr., Rio, Ayana, Mister & Heavenly

Not that everyone gets a choice: In many areas, schools are only offering one option. As of August 6, 13 of the 15 largest school districts in the U.S. have opted to remain online-only in the fall. Other districts plan to offer hybrid options, a mix of in-person and at-home learning.

Ayana Alvarez’s school district in Eastvale, California is starting the year with remote learning. She has three school-age children, teens Mister and Daryl Jr., and 9-year-old Rio, who has multiple life-threatening food allergies and asthma. Alvarez worked closely with Rio’s school for years to implement food safety measures in the classroom, regular use of hand wipes and cleaning Rio’s desks and computer keyboard to protect against allergens. “A lot of the things we did for food allergies translate really well for COVID,” she notes.

Yet, even if classroom instruction becomes an option later, none of Alvarez’s children will be heading back to school in-person anytime soon. In past, Rio has been hospitalized four times for pneumonia. Seeing Rio in the hospital was a nightmare, “so anything I can do to prevent that is what I will do,” she says. Plus, Alvarez’s son Mister is going into his freshman year at a large high school, and his mother isn’t confident that the school will be able to protect against the virus.

She’s told her boys, “if Rio can’t go, none of you can go, because I can’t allow you to bring COVID-19 back here.”

and Francisco ‘Frank’ Pagés

Miami mom María Pagés, whose son Francisco has multiple allergies, is taking a similar approach. Fransisco will be starting 7th grade this year at home. With the high rates of infection in Miami, she says even going to the grocery store feels like a risk.

Pagés says the way her family approaches life with allergies now extends to COVID-19. “It’s not ‘living with fear,’ we see it as ‘proceeding with caution,’” she says. “We teach our son not to focus on what he can’t do, instead find a way to do the things he enjoys, safely.”

Some COVID-19 measures, like frequent handwashing and disinfecting surfaces, also help to protect against allergen exposures. Due to the pandemic, the school has also hired a school nurse, which Pagés considers a “great plus.” But she is not ready to see her child in a classroom yet. “It’s not worth the risk,” she says.

A Teacher’s Difference

and face shield.

Francisco and Rio are both children who adjusted well to at-home learning, but that hasn’t been the case for all students.

“Believe it or not, I want her to go to school,” says Irvine, California mom Shannon Bui, speaking of her daughter Savannah, who is set to start kindergarten in late August.

Bui, who works as a nurse’s assistant at a local hospital, has been practicing safety measures, like wearing a mask and frequent handwashing, with her 4-year-old. She’s confident that her daughter will be able to continue these practices at school. Yes, the students will be eating in their classroom. But Bui notes that with social distancing measures, Savannah, who is allergic to peanut, pistachio and cashew, will be at her own desk, away from other children when they are eating, and under the supervision of a teacher.

These measures, in addition Savannah’s good understanding of her food allergies, have made Bui feel more comfortable about safety in the classroom. Though their California school is starting the year online, Bui plans to send Savannah to an in-person kindergarten if that becomes an option.

“I think it would be really good for her to learn, and be in a structured environment,” she says. “I’m not giving her structure at home.” Bui would meet with the school principal, nurse and Savannah’s teacher about her daughter’s 504 plan accommodations. Depending on the allergy precautions and protocols that are in place, however, she may yet reconsider.

Encouraged by Class Size

Frankie and Mia Giuliani

Food allergy mom Erica Giuliani has faced a similar challenge in Tinley Park, Illinois. At 5 years of age, her daughter Mia doesn’t fully get the concept of online learning. She would leave during a lesson, when she didn’t want to watch the screen anymore. Giuliani worries that she won’t be able to help Mia excel the way she could in school. “More than anything, I want that one-on-one assistance with an actual teacher versus me trying to do it all on my own,” she says.

Giuliani wrestled with her own reservations about classroom learning. She imagined classes the way they were back when her son entered kindergarten, with 30 children and one teacher. If Mia, who has multiple severe food allergies was wearing a mask, would it be harder to notice symptoms like hives and swelling?

On Facebook, allergy moms encouraged Giuliani to speak with the school administrators. She soon learned that at Mia’s school, in-person class sizes would be kept between seven and 10 students. The school was also able to provide a mask with a clear window, easing concerns about Mia’s symptoms being seen.

Although students will be having snacks and lunches in their classrooms, in keeping with the CDC’s COVID-19 recommendations, desks will be spaced apart and sanitized before and after eating. “It’s going to be a lot more controlled than what I was worried about,” says Giuliani.

Eating in the classroom is a hot button issue for many food allergy parents. In the meeting for Mia’s 504 disablity plan, Giuliani intends to ask for measures to be spelled out, such as avoidance of certain allergens in class lunches and specific handwashing protocols.

As a food allergy parent, Giuliani says “the worry is always going to be there,” but working with the school administrators has helped to ease her concerns. “Instead of putting all that worry on yourself, reach out to the school and get a plan that works for you,” she says.

Related Reading

Safe at School: Navigating COVID-19 and Food Allergies

CDC’s Schools & Coronavirus website

COVID-19 and Food in the Classroom

Johns Hopkins’ States and School Reopening Tracker