Clues that plants are allergy-friendly: doubling of petals on blue rose-of-sharon. Photo: Courtesy of www.provenwinners.com

Clues that plants are allergy-friendly: doubling of petals on blue rose-of-sharon. Photo: Courtesy of www.provenwinners.com Expert Thomas Ogren spills the secrets of how his allergy-fighting garden grows – and how yours can too.

THOMAS Ogren is a self-professed sexist – at least in the garden. The horticulturist, teacher and author prefers female plants of most species because it’s the male plants that expel enormous amounts of pollen into the air – triggering allergic symptoms from sneezes to watery eyes, congestion and even asthmatic wheezing. And the girls of the various species? They’re the ones cleaning up, Ogren says. “Female plants make no pollen, and they always trap it.”

But while gender selection is a starting point for allergy-friendly gardening, things quickly get more complex. This has led Ogren to spend decades researching and writing to make it easier for gardeners to understand which plants will set off allergies and asthma and, importantly, which ones won’t. He has authored two books on the topic, including The Allergy-Fighting Garden.

The horticulture and landscape design instructor also devised the unique Ogren Plant Allergy Scale – or OPALS – which translates his body of research to a 1-to-10 ratings system to help gardeners and growers alike to pinpoint a plant’s potential to trigger allergies.

“When I first started doing research in this area, nobody in horticulture thought about things in this way,” he says. “They always talked about plant health, but they never talked about human health.”

Allergic Living speaks to Ogren on everything from how to neutralize the pollen of male trees to visual clues that a flower is allergy-friendly, and picking the best allergen-blocking hedge.

Why did you first become interested in allergy-fighting plants?

Horticulturist Thomas Ogren

Horticulturist Thomas Ogren Thomas Ogren: I met my wife, Yvonne, when she was 15 and I was 17. She’s a terrific lady, and we’ve been married 48 years. She has terrible asthma and mind-blowing allergies.

But back then, I believed that her allergies were mostly in her head, so I was not very sympathetic. She had a serious illness and I was telling her, “Oh, get your act together.” It was arrogant and stupid of me.

Then while teaching classes [in horticulture], I started noticing students having what looked like allergic reactions. So I started doing “sniff tests” with students, probably about 30 years ago. On the first day, we used a plant called the bottlebrush. A third of my students started sneezing like crazy off of just one sniffle. As soon as that happened, I realized I was full of crap about my wife’s condition.

Other than apologizing, what did you do next?

Ogren: I went home and told my wife, “I am going to take our yard, and I am going to get rid of everything that’s allergenic, and I’m going to replace it with something that’s not. I’m going to make you an allergy-free yard.”

But when I went to find out how to do it, I couldn’t find a thing. I was trying to explain to one research librarian what I was looking for, but she laughed and said, “Well, it is gardens that make people have allergies!” So I said to her, “Some plants do, and some plants don’t. And I want to know the difference.”

What are the first steps someone can take to transform their yard?

Ogren: I would try to identify the very worst plants in the yard, if indeed there were any. Any type of foundation plants that are underneath bedroom windows are really crucial, as well as plants closest to doors.

Are there visual clues to signal that a plant is less likely to be a pollen problem?

Disease-resistant and scent-free, Pink Grootendorst is also hardy. Photo: Getty

Disease-resistant and scent-free, Pink Grootendorst is also hardy. Photo: Getty Ogren: If you see any kind of berry or fruit on a shrub, tree or other plant, you know, if nothing else, that it’s not an all-male plant. On the other hand, if it has any words like “seedless” or “fruitless” or “litter-free” in its name, then that’s a warning to leave it alone.

Another clue is that there are plenty of flower species for which growers have been breeding to get more petals – called doubles and super-doubles. What often happens is that every time you get an extra petal, you lose a male stamen, and eventually the whole flower becomes “stamenoid” – meaning that the stamens look a little bit like stamens, but they’re not functional. Generally, the more petals a flower has, the less viable pollen it has. This is true with hundreds of different flowers. Many plants that have highly doubled-up flowers – for example a rose-of-sharon that doubles – won’t produce any allergenic pollen at all.

What factors can help someone determine if a plant is likely to be allergy-friendly?

Ogren: One of the first things I ask when I look at a plant is: What family is it in? Who are its relatives? Certain groups of plants tend to have more allergenic tendencies. All pollen is not created equal: certain types of pollen are 100 times more allergenic than others.

Anything that is related to the euphorbias (poinsettia, milk- bush, gopher plant, crown-of-thorns) is likely an allergy trigger. If you’re considering a plant from the huge anacardiaceae family – the cashew family, which includes poison sumacs, poison oaks, and tens of thousands of other species – it’s not a slam dunk that it will be a bad plant for allergies, but it’s a red flag.

The rose family, on the other side, is huge, and it does have allergy plants in it, but it isn’t a red flag plant family. For the most part, it’s a good sign to be related to roses. On a [pollen] grain-for-grain basis, it’s not a particularly allergenic group.

What about insect vs. wind-pollinated plants? Is there a clear rule that the former are less allergenic, and easy ways to tell the two types apart?

The Cecile Brunner pink climbing rose is easy on the eyes and airways. Photo: Corbis

The Cecile Brunner pink climbing rose is easy on the eyes and airways. Photo: Corbis Ogren: The idea that big, pretty flowers [often a sign of insect pollination] are less likely to cause allergies is of some value. But prime exceptions also come to mind: a chrysanthemum flower is big, beautiful, highly colored and attracts insect pollinators but, because it is related to the ragweed group, it is right away somewhat suspect, and indeed, mums often trigger allergies. I would caution readers that many of those exceptions are pretty common landscape plants, and if you’ve got too many of them in your garden, you’re asking for problems.

A question I ask is: “What do existing allergists’ data from skin or sniff tests show?” and “Are many people allergic to it?” No matter how colorful the flowers are, or how many insects visit it, a plant can still have considerable allergic potential. Having said that, almost all plants that are 100 percent insect-pollinated pose less allergic potential.

In The Allergy-Fighting Garden, you mention that an allergy to a rose’s scent is more common than allergies to the flower’s pollen. Which varietals are best then?

Ogren: Roses should be adapted to growing well where you are. Also, there are certain types that are pretty much male sterile: They just don’t make any pollen. A common rose in Florida or California or anywhere it is fairly mild – they wouldn’t grow well in northern climates – is the Cecile Brunner (or Sweetheart Rose), a climbing pink rose with some fragrance, but that doesn’t make any pollen. Carefree Delight, on the other hand, is pink and hardy to zone 4 (-25 to -30 degrees F), with no fragrance.

A nursery's sign displaying the OPALS rating system. Photo: Getty

A nursery's sign displaying the OPALS rating system. Photo: Getty In addition, the following roses are hardy up to wintry northern climates like Chicago or New York, and are also disease resistant and free of fragrance, which are big pluses for allergy avoidance: F.J. Grootendorst is an old rose, bright red and lots of petals; Pink Grootendorst is a tough flower; William Booth is red with a white center; Hope for Humanity is red and very hardy.

Can you explain the OPALS system and its genesis?

Ogren: OPALS started out as a time-saving device for when people interested in allergy would ask me about different plants for the garden. I needed to be able to rank these plants, so I set up a criteria list of pros and cons for each plant, and gave each one a single numerical value corresponding to its position on a scale from best to worst for allergies. Then when people asked: “Well what about this bush?” I could respond, “Well, 1 is the best and 10 is the worst and this one is a 5.” Right away, everybody understood that.

If you have a heavy pollen-producing male tree and you’re not able to remove it, what can you do instead?

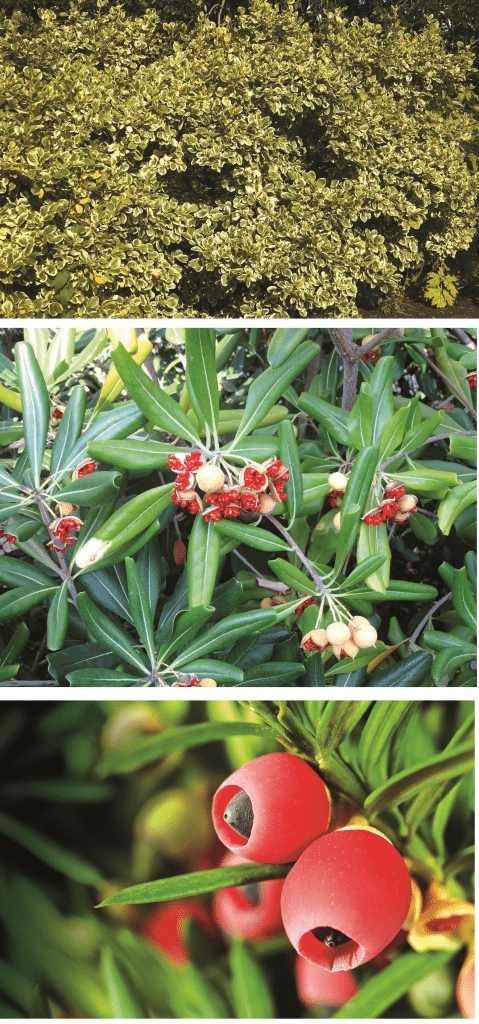

Top: Griselinia Littoralis is excellent as a pollen-catching hedge. Female pittosporum (middle) and yew are good choices, too. Photo: Thinkstock

Top: Griselinia Littoralis is excellent as a pollen-catching hedge. Female pittosporum (middle) and yew are good choices, too. Photo: Thinkstock Ogren: Plant a female really close to it, particularly on the side where the wind is going to blow pollen from the male tree. If that’s not possible, try to plant a female tree of the same species between the male tree and where you’re living. Then the female tree will catch most of that pollen.

There are also pruning techniques you can use to cut down the amount of pollen. Heavy pruning on an annual basis will almost always knock a huge amount of pollen off a male tree. Also, on a lot of different male trees that are very allergenic, such as birch and alder, almost all the pollen cones will be on the tips of the branches. So if you had 10 to 12 inches of the tips pruned off in the fall, the following spring you would have very little pollen.

Your book highlights hedges for catching and blocking pollen. What are the key factors for deciding on a type and location?

Ogren: For a border hedge, you want to use a species that’s already common in your area, and a female version of it. Say you’re living somewhere in a southern area, like Los Angeles, where they have lots of pittosporum. That means there will be plenty of pollen from those species of shrubs and trees, because so many of them are male.

If your pittosporum hedge is female, it will trap the most prevalent kind of pollen in your neighborhood. If you live in a northern area, where a lot of people plant yews – lots of those are likely to be male, so a hedge of female yew would be ideal for the same reasons.

One of the worst mistakes people make is that they plant tall evergreen things on the south sides of their yards. In the wintertime, that blocks out the low light you need, keeping everything cold and damp. So the tallest hedges should generally go on the north side.

Is there one tree, flower or shrub that someone living in a southern or northern climate could add to their garden to improve its allergy-fighting capabilities?

A female permisson tree is one of the best plants to grow.

A female permisson tree is one of the best plants to grow. Ogren: For its wide coverage across different species, I’d pick a persimmon tree. You can get persimmon trees that would grow in Los Angeles, and ones that would grow in northern climates, too. Persimmon trees are also 100 percent dioecious – they’re either all-male or all-female. And if they have fruit, they’re all female, which means no pollen.

They also have one of the best fall colors you’ve ever seen. Among the fruiting types, a lot of them make fruit with what’s called parthenogenesis, so they don’t even need to be pollinated. A tree like that is always a wonderful addition to anybody’s yard.

See more about Thomas Ogren’s book here.