They may not know each other, but they have something very much in common. For as long as they can remember, Kwame Baird from New York City and MaryPat Weir of Ramsey, New Jersey have suffered with eczema. The painfully itchy rash disrupted their sleep, and left each of them feeling frustrated and demoralized.

Both are also teachers, who had to get used to answering questions from curious kids about what was wrong with their skin.

For decades, they had used topical steroids and periodic oral steroids. But nothing brought lasting relief.

That changed after they began taking a new medication, upadacitinib (the brand Rinvoq) as part of a clinical trial. The daily pill is among a new class of eczema drugs which recently gained U.S. Food and Drug Administration approval. Dermatologists say the powerful drugs, known as JAK inhibitors, are the most effective medications for atopic dermatitis (or eczema) introduced in decades.

JAK inhibitors block the action of a family of enzymes, Janus kinases (JAKs). These enzymes are involved with messaging on a pathway among immune cells and cytokines, which are molecules that kick off inflammation and itch. By disrupting JAK messaging, the medications suppress cytokines, reducing eczema symptoms.

The FDA approved three JAK inhibitors for eczema: upadacitinib and abrocitinib (Cibinqo), both once-daily pills, and ruxolitinib (Opzelura), a skin cream.

The pills are recommended for people with more severe eczema that is not well-controlled with other oral or injectable eczema medications. Upadacitinib is okayed for adults and children ages 12 and up; abrocitinib is for adults only. The cream is aimed at mild to moderate eczema, and approved for adults and children 12 and up.

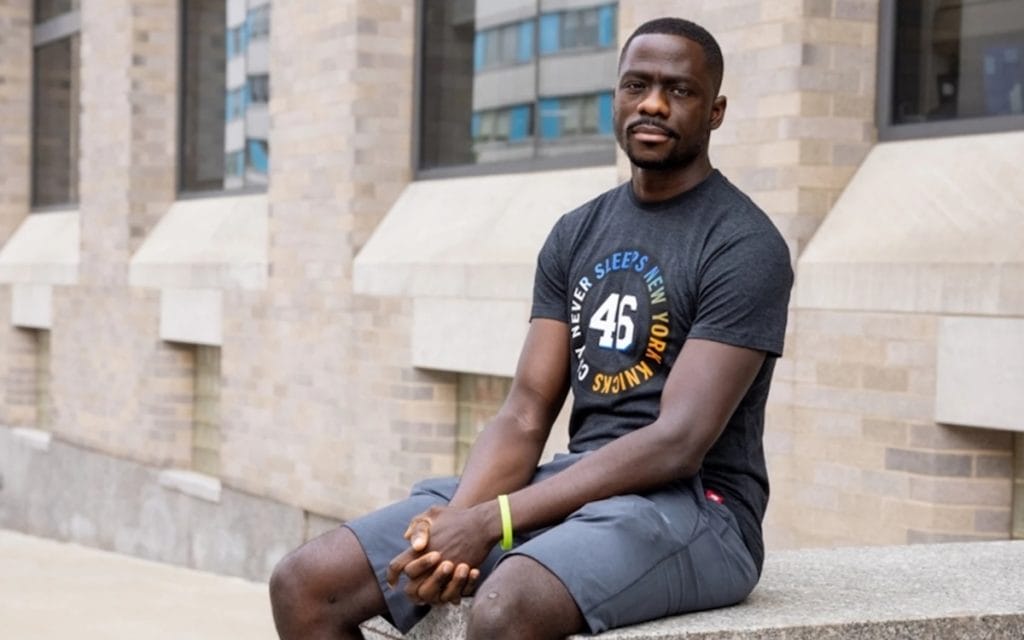

Kwame Baird’s Story

Some of Kwame Baird’s earliest memories are of taking oatmeal baths and slathering on lotions and ointments to soothe his painfully itchy skin. “As a kid, I thought it was normal for people to itch or scratch all the time,” says Baird, who’s 39. In middle school, “when I compared my skin to other kids, it was discolored and patchy.” That was when “I started to realize my skin was different,” he says.

When he went away to college, Baird’s eczema got worse. He wore gloves at night to try to stop himself from scratching in his sleep and waking up with raw and bleeding skin.

“There were days when I was scratching myself so bad, I could hardly walk from all the aches,” he says. “I carried on like that, itching all the time.”

He sought treatment, but “every doctor would tell me the same thing: ‘Try not to get too dry. Try not to sweat too much. Use a prescription steroid. Don’t use it for too long. Just use it in spots for a couple of weeks and then leave it alone.'”

The pain and itch would improve temporarily, only to come roaring back when he stopped using the creams and oral steroids. Baird enrolled in a clinical trial for an injectable eczema medication, but for him, there was no benefit.

As a father with two young children and a high school English teacher in the Bronx, Baird started worrying about how he would continue to cope with eczema’s misery. As a result of his cracked skin, he got a serious skin infection that sent him to the hospital.

A dermatologist recommended that he enroll in the New York clinical trial for upadacitinib, being led by Dr. Emma Guttman-Yassky, chair of dermatology and immunology at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. After a month on the medication, Baird’s itch was much better. Three months later, he wasn’t itching at all. The bumps and patches on his skin began to clear.

Baird started wearing short sleeves and bright clothes, which he had long avoided because of his flaking skin. “The biggest thing is the mental health,” he says. Freed from the itch, he realized what a burden the condition had been.

“Maybe every once in a while, I feel a little bit of an itch, but it goes away when I put on some cream or lotion.” Being on the JAK inhibitor, “has completely changed my life.”

MaryPat Weir’s Story

“I don’t remember not having eczema,” says MaryPat Weir, a 62-year-old special education teacher with two grown children.

Throughout her childhood, Weir kept her eczema at bay using topical and at times, oral steroids. But when she was pregnant with her first child, doctors advised her to stop using steroids. This led to the worst eczema experience she’s ever had.

Her skin became so cracked, itchy and painful, she spent two months on bedrest. “I was in bed with ice packs. By the time he was born, they had to give me shots of prednisone to try to get back to the point where my skin could even hold the baby,” Weir recalls.

And decades of steroids had left her with damaged and thinned skin.

In 2019, Weir developed alopecia areata, the autoimmune disorder that causes rapid hair loss. Over about a week, her hair fell out in clumps, leaving her suddenly, and completely, bald. “It was traumatic,” Weir says.

A friend whose daughter had experienced the disorder recommended she see Guttman-Yassky at Mount Sinai.

“I went for the hair loss but Dr. Guttman-Yassky looked at my skin and said, ‘You have eczema,’” Weir recalls. The dermatologist recommended that Weir participate in a clinical trial for upadacitinib to treat her eczema. And, as luck would have it, studies have shown that JAK inhibitors can also help hair regrow in people with alopecia.

Initially, Weir was assigned to the group given the placebo. Unable to use steroid creams, it was a difficult few months of itchy skin and a drastically altered appearance. The wig she wore made her scalp and neck itch mercilessly.

But she stuck with it, and four months later, was eligible to get the active medication.

“Within a month, my skin was remarkably better,” she says.

Within a few months, “my face was completely clear. The back of my neck was clear. The backs of my knees were clear. I didn’t have patches anymore.” Weir’s hair also started growing back, a huge relief. “The effect of the medication was such a psychological and physical boost,” she says.

Related Reading:

3 Newly Approved Eczema Therapies Called ‘Game-Changing’

Ask the Dermatologist: Over-Use of Steroids Caused My Eczema to Spread

Ask the Dermatologist: Can Aloe Vera Make Skin Break Out in a Rash?